Anime is beloved world wide yet there is one issue that is often overlooked when it comes to it’s universal approach.

Anime is a thirty-one billion dollar industry. Praised for its complex, unorthodox storytelling and eye catching style that is beloved by fans across demographics and nations. Part of the reason experts believe this medium and it’s companion, manga, have grown well beyond the limits of Japan is due to it’s universal appeal represented in the seemingly limitless potential the industry has to capture the attention of regions as vast as South East Asia, the Pacific Islands, Australia, Europe all the way to North and South America.

Despite the endless success that only seems to grow each year, there is one factor in anime design that I believe deserves to be re-examined. The key to the industries success – universal character design and it’s struggle with colorism.

Colorism – Anime Characters are Raceless not Colorless

The debate over the race and ethnicity of anime characters is a surprising one considering that anime and manga are of Japanese origin. So it would make sense that most if not all characters by default are Japanese. However that is not always the case.

Industry veterans have claimed to purposely steer away from designing their characters to look like Japanese people. While others take inspiration from other cultures, folklore, and settings found outside of Japan. Mixing Japanese names or sentimentalities with environments not local to Japan itself. The more creative anime and manga get with this mixture of culture and ethnicity, the more blurred the lines seem to become when determining the exact identities of their characters. Because of this unique approach, it might be fair to say that many anime characters don’t actually have a racial identity as they don’t tend to operate by the rules of our world. However, where these characters seem to lack race, they are still made with color. And color is just as subject to bias and discrimination as race alone. Hence where the issue of colorism in anime becomes a problem.

Like any ism, colorism is a word that packs a lot of heated debate. Coined by author and activist Alice Walker in 1982. Its definition is discrimination on the basis of skin tone caused by an implicit bias that favors lighter skin. So you may think it’s impossible for colorism to exist in anime, manga and gaming, considering that the locations of where this popular media originates have people with a similar ethnic makeup.

But it’s important to acknowledge that not only is there still a prevalent range of ethnic features found in East Asian countries, but also that colorism crosses ethnic and racial boundaries and has, subconsciously or otherwise, been spread globally making it common in everyday life and media, even in anime. However, colorism in anime is something that can’t be accurately discussed without first breaking down the complicated concept of mukokuseki and where it stems from.

Defining Mukokuseki

In Recentering Globalization: Popular Culture and Japanese Transnationalism Koichi Iwabuchi breaks down the conflicting nature of Japan’s cultural influence, the county’s history of imperialism, their existence as an “othered” Asian country, their role in WWII, and the West’s (particularly Europe and the United States) heavy influence on their nation. Considering all of these topics, Iwabuchi explores how Japan uses it’s culture as a way to spread their influence in a non-threatening way that appeals to Western sentimentalities of Asia. The reason this works is mostly due to Orientalism – a stereotypical way that Western countries view Asian countries as a whole. Because it always leads back to stereotypes and discrimination. Sigh. Let me not get ahead of myself.

Iwabuchi’s exploration of Japan’s ambiguous identity as a geographically Asian country perceived as above other Asian countries yet historically dominated by the West is the essential lead up to understanding the concept of mukokuseki and how Japanese products became global successes.

Iwabuchi describes mukokuseki as “literally meaning ‘something or someone lacking any nationality,’ but also implying the erasure of racial or ethnic characteristics or a context, which does not imprint a particular culture or country with these features”(Iwabuchi, K. (2002). Recentering Globalization: Popular Culture and Japanese Transnationalism. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv11vc8ft).

Though Iwabuchi uses the term to explore Japanese exports beyond media and entertainment, this is fundamental to understanding how anime came to be a global success.

To explore this term in anime and manga, Mukokuseki can refer to characters in Japanese works, or sometimes the work itself, not having an ethnic identity and being seen as “stateless” or “odorless” indicating they do not represent any one culture. This is even a concept that extends outside of Japanese media, as many books and even shows and movies across the world rely on the idea of characters who are either “default” or “up to interpretation” by the consumer of that media.

For example, when a character’s looks are described with little to no details in a novel, it is often implied that they are the default of whatever the reader’s culture or race or up for interpretation as the reader sees fit. Another example is when a character in a modern movie or tv show adaptation is played by a racially ambiguous actor with no insinuation of their ethnicity being mentioned in the story. This is a tactic often used to make a piece of media “universally marketable”, easier to digest for new or unfamiliar fans, and therefore more profitable. Yes, I’m keeping the term “universal” in quotes for a reason.

Anime and manga utilize mukokuseki by simplifying facial features and exaggerating hair, eyes, and clothing. Though mukokuseki essentially means statelessness, it does not mean without personality. Meaning that anime and manga characters are often bold and vibrant as artists and animators use a variety of characteristics and styles to represent the aura of their characters.

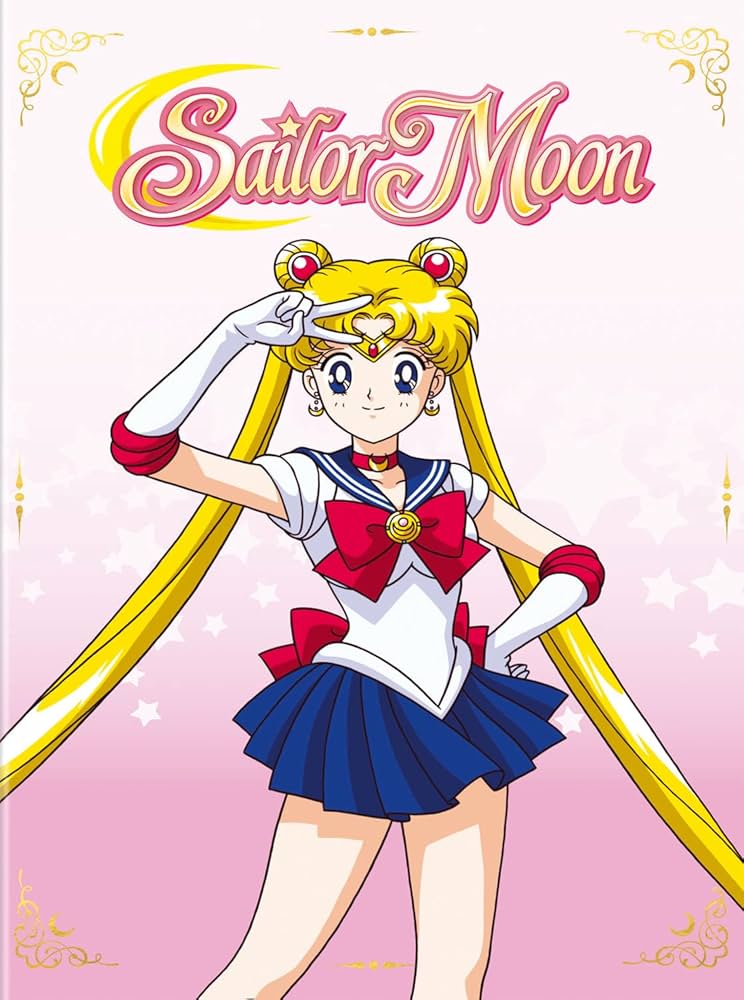

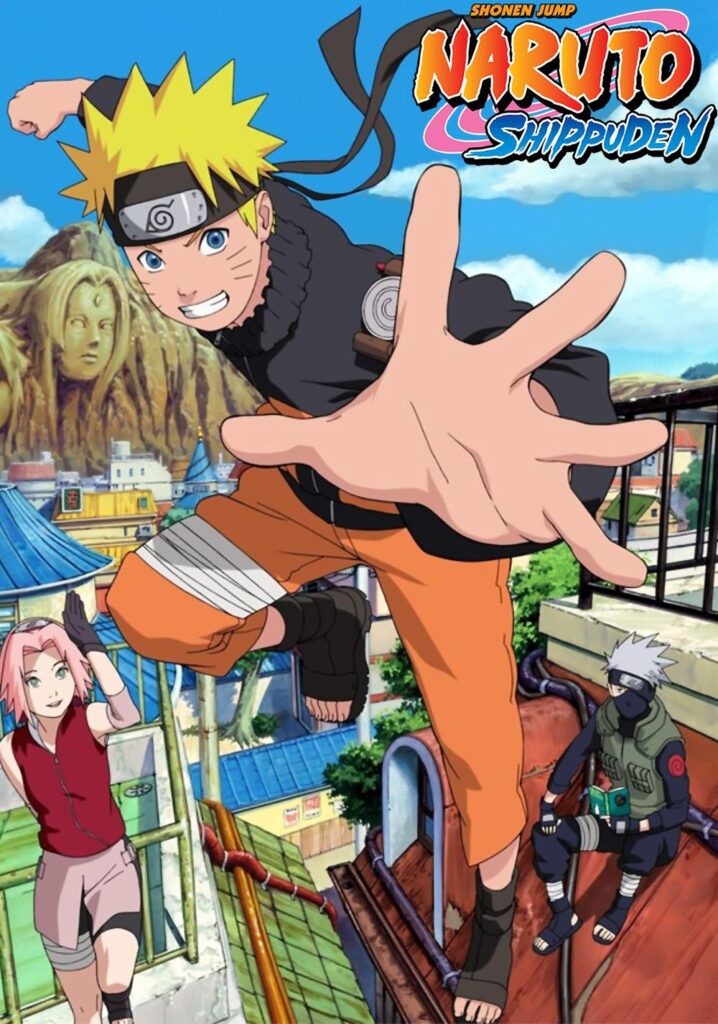

For example most anime characters would be considered Japanese, especially if they have Japanese names or if the story is set in Japan or heavily based on it. Yet many main characters of series like this have hair styles and eye colors that are not common of Japanese people. Let’s play a game of “Guess What These Characters Have in Common!” Can you spot the similarities between these three character designs?

Besides being from globally successful series, they all have similar hair and even eye colors and all might be considered Japanese. But what really stands out is they’re hair and eye colors. Some of these are explained by the characters dying their hair, being struck by lightning, or even being mixed-race but most of the time there is no explanation for a character having blond hair or blue eyes other than the creator wanting to make them visually distinct using mukokuseki. This “statlessness” became a popular concept in media as it made it easier for Japanese fans to keep the mediums separate from their own reality, essentially transporting Japanese audiences to alternative dimensions through animation. In essence Anime as a whole is Isekai. Yes, I’m being serious.

In Anime from Akira to Princess Mononoke – Experiencing Contemporary Japanese Animation Susan J. Napier writes about director Mamoru Oshii (Ghost in the Shell) and his thoughts on how anime is “De-Japanizing” stating, “Oshii suggests that this is part of a deliberate effort by modern Japanese to ‘evade the fact that they are Japanese,’ quoting a provocative statement by the director Miyazaki Hayao to the effect that ‘the Japanese hate their own faces.’ Oshii sees the Japanese animators and their audiences looking ‘on the other side of the mirror,’ particularly at America, and drawing from that world to create, ‘separate from the reality of present day Japan, some other world’ (isekai).” Napier, Susan Jolliffe. Anime from Akira to Princess Mononoke : Experiencing Contemporary Japanese Animation. New York :Palgrave, 2001.

The lack of ethnic features in media coupled with the idea that animation was easier to disseminate to western audiences than live media featuring Japanese actors, is often attributed to the reason anime, manga, and gaming became such a global success outside of Japan in the early 2000s. “Such export enthusiasm in its early days was based on the worldwide success of Disney’s animation films, as well as upon the assumption that animated films would have a better chance of succeeding in the West than live-action films featuring Asian actors,” said Kaichiro Morikawa an anime expert at Tokyo’s Meiji University in an interview with CNN.

Mukokuseki made it easier for what Japanese creators considered a “global audience” to default the characters to their own physical attributes. Notable animators with blockbuster hits like Osamu Tezuka (Astro Boy), Masashi Kishimoto (Naruto), and Mamoru Oshii, among others, attribute mukokuseki to the success of their works with a global audience. This is proven mostly true as series with blond-haired, blue-eyed characters are often popular with western viewers.

Oshii claims his character’s designs and features are purposely based on Caucasian features and Tezuka has credited the influence of western culture and art styles for the success of his works overseas. Kishimoto stated in an interview that he was happy that he gave his titular character blonde hair and blue eyes because it helped to make his series successful in America. Outside of animation, massively successful games like Pokémon, Sonic the Hedgehog and Super Mario Bros each found success by not presenting as Japanese. With game revenue coupled with multiple movie adaptations for these franchises reaching billions of dollars because of their universal appeal. Except in the early 2000s when people believed in the whole Pikachu is the devil thing.

Ambiguously Brown – Not Black

Wild hair and large colorful eyes are not the only ways creators utilize mukokuseki. Skin color is also a way of adding “flavor” to a character. The most recognizable flavor of brown character is what I like to call mocha with a dollop of whip cream, more commonly recognized as brown characters with white hair. These designs are meant to stand out more than conform to a certain identity though they sometimes have hints of inspiration from other cultures. Think of characters like Miriko from My Hero Academia, Archer from Fate/Stay Night Unlimited Blade Works, Scar from Full Metal Alchemist, Noé from The Case Study of Vanitas, Karako from Deadman Wonderland, and almost any dark-elf character. The list of characters with these traits is almost exhaustive yet still pale in comparison to the amount of fair-skinned, light-haired characters that exist in anime alone.

There are even a few characters with dark skin and dark hair that are not really meant to represent any real life ethnic group. Such as Yoruichi from Bleach and Casca from Berserk in which the mangaka for the latter, Kento Miura, once stated that he gave Casca dark skin simply to make her stand out from the other characters. Arguably the ambiguously brown character trope is successful in its own universal appeal (though on a much smaller scale because there are fewer of these characters) as many fans with similar features love to claim these characters as their own. Hence why black online communities are obsessed with characters like Yoruichi from Bleach and Mirko from My Hero Academia (including myself, as I have a posters of both that you sometimes see behind me in videos).

But taking mukokuseki into consideration, even fans of this small but prevalent group of characters have to come to terms with the fact that they are not actually representing black or brown people. They’re just wearing our skin. Especially when the audience is never given an explanation as to why a character has a darker skin tone.

These ambiguously brown characters are not to be confused with ones that undeniably represent real people and cultures. Such as Indian characters Agni and Shoma (Black Butler), Afro-Brazilian inspired Mitchiko Malandro (Mitchiko to Hatchin), and Carole who is of African-American descent (Carole & Tuesday), among others. There is an entire complex history of representing real ethnicities and nationalities in anime that I don’t have time to cover here but I highly recommend BasicBoi’s videos on the topic.

The Problem With “Universal” Design

Mukokuseki seems like a perfect way for artists to create visually interesting characters without referencing complex issues like race. These designs reach a global and universal audience that has turned anime into a multi-billion dollar operation in several major countries around the world. So how exactly is anime colorist if the characters are meant to be stateless and lack ethnic characteristics?

Despite mukokuseki sounding like the solution to discrimination in media, we unfortunately can’t ignore two major discrepancies. The first is that universal appeal of mukokuseki character design insinuates that the “default” is often fair-skinned and light-haired. The second, is that characters given mukokuseki features often reinforce stereotypes including those that favor characters with fair skin and disregard darker skin individuals. These stereotypes have permeated media for well over a century.

Before someone says it, I will acknowledge that there are endless varieties in not only hair, face and skin but also monster or animal hybrids and absurd styles and concepts that don’t reflect reality in any way. However, we can’t deny that popular series that utilize mukokuseki, tend to have characters that default to fair-skin and light hair which is why this is an issue.

Sarah-Anne Gresham’s article Black Bodies at Play: Race and Gender at the Edges of Subjectivity explores the conflicting nature of mukokuseki and how leaning into universality only continues to promote the illusion that dark skin and ethnic features outside Eurocentric standards are not universal. Gresham states, “Allusions to nationless-ness and neutral-looking characters who bear no relation to any specific race or ethnicity inadvertently reanimate harmful racial paradigms that historically presented Whiteness as neutral, default, and politically innocent” (Gresham, Sarah-Anne. “Black Bodies at Play: Race and Gender at the Edges of Subjectivity.” Mechademia, vol. 17 no. 1, 2024, p. 93-117. Project MUSE, https://muse.jhu.edu/article/946210).

We also can’t deny that the most popular series have a track record of depicting common biases of real people. Blond hair is almost always given to heroes, heroines and characters that are either innocent or immensely powerful. Dark skin is generally given to mysterious, mischievous, forgettable, or just downright evil or violent characters. Sometimes characters that are referenced to be dead have dark skin. Such as in Bleach Thousand Year Blood War or the Fate/Stay Night Unlimited Blade Works franchise. There is also a trend of including senselessly violent and sexual acts on darker skin woman as their sole character arc such as with Casca (Berserk) and Karako (Deadman Wonderland).

It’s gotten to the point that self proclaimed Aryan users on social media believe anime depicts the pure white-only society that they long for. Which is a wild concept considering these works are Japanese. If most designs in anime are supposed to be stateless, how is it that a medium made by and for Japanese people is seen by alleged Neo-Nazi users as a depiction of a reality they crave? If mukokuseki is used to purposely alter reality, then why are characteristics like skin and hair color used in such a stereotypical way?

The answer lies in Hollywood. It’s no secret these are common tropes and stereotypes of people with these features that have appeared in successful Hollywood movies for decades. Movies that have been criticized by American audiences for depicting dark skin people as being violent criminals, loud, rude, sexually explicit, or simply forgettable while fair-skin, light haired heroes are the main characters and deemed as attractive saviors or sometimes simply divine. These same movies have also found popularity in East Asia.

We should also consider Japan’s own complex history in which the country’s historical desire for imperialism and how it was used and subdued by Western imperial forces, has influenced the perception Japanese people have on their own society. Within this history lies a preference for pale skin in beauty, and the erasure of native and island people including Ainu and Ryukyu people who were conquered by the country and have had aspects of their culture destroyed or hidden. These native people once included and still include individuals with features that are distinct from the image of Japanese people we know today, yet are rarely represented in anime or manga.

So though mukokuseki is meant to be a “stateless” way to design characters, there are glaring issues with it’s use as it perpetuates the falsehood that light skin is the global default. While also continuing to use colors in a way that insinuates bias. Hence why I believe anime is capable of being colorist, despite it’s characters technically being raceless and stateless.

An important thing to note is that colorism is often implicit. Meaning though it is not always openly addressed or purposely done, it still exists. Media that originates from various areas of East Asia may not purposely be insinuating negative bias and stereotypes towards darker skin people but that does not mean that they are not still contributing to the global idea that people with these features are often ignored, or viewed in a negative or questionable light. Which is harmful whether its purposeful or not.

Understanding Mukokuseki is just breaking the tip of the iceberg on this topic. In the next post, we will explore ways in which video games and even fandom continue to fall into the mukokuseki colorism trap.

So What’s the Answer?

So should anime be truly universal? Despite everything we explored, I don’t quite have an answer to this.

I believe that anime is allowed to have fun with it’s character design and setting. The wild styles and colors are an inherent part of what makes anime and manga special and I don’t want that to change. Additionally there are many stories featuring characters that are Japanese, with Japanese features. As well as stories representing specific ethnic groups some based on historical people. These stories shouldn’t be held to the same standard as ones set in fantastic worlds or ones with characters that are heavily influenced by mukokuseki.

However, if the main goal for the companies producing these franchises is to achieve a global, universal, profitable audience using mukokuseki in some of their series, then I believe that it should in some way encompass characters that have features that are truly universal. Features that exist across the diaspora of people who do not all have pale skin, light hair, thin lips or small noses. Because in order to be truly universal, these designs need to embody the diverse existence of people that not only exist in our world, but are prevalent in the audiences that watch and read them, while also being respectful.

The anime industry is slowly making more progress towards putting characters of various skin tones and even ethnicities at the forefront of their series. In past five years we’ve gottens series like The Case Study of Vanitas, Carole and Tuesday, and Metallic Rouge among others who each have main characters or even protagonists with varying skin shades and ethnic backgrounds. More stories with these characters and others, are being welcomed by fans overseas. Couple this with the fact that companies like Crunchyroll and Netflix are throwing money at concepts that specifically appeal to audiences in their most profitable countries, the U.S. for example, where we get entire franchises with English theme songs and stories that feature diverse characters are often among the most popular. Think of Delicious in Dungeon, one of the biggest anime on Netflix in 2024. Though only inspired by anime, in 2023, the live action adaptation of One Piece featuring Mexican actor Inaki Godoy amassed 72 Million views and remained on Netflix’s Top 10 list for 8 weeks in a row according to a Collider article.

At the end of the day I don’t believe or trust anime and manga to accurately represent people who look like me or other people who are not considered to be “the default.” Which is why I consume other media where I feel properly represented. I also don’t need anime and manga to portray people like me in order to enjoy it. However, as long as anime benefits off the global success of anime fans around the world, I will always want for there to be better representation of diverse people in their works. And I will hold them to higher standard when it comes to that.

If you want to learn more about how mukokuseki plays a part in the controversial argument over race bending in fan art please check out this video. Thank you so much for reading. Until next time, peace!